The Return of the California Condor

The California condor almost reached extinction due to poaching, lead poisoning from eating animals shot by hunters, and destruction of its habitat. But the restoration of wild condor populations has been a success. A central piece of the story that is often left out: this effort was Indigenous-led.

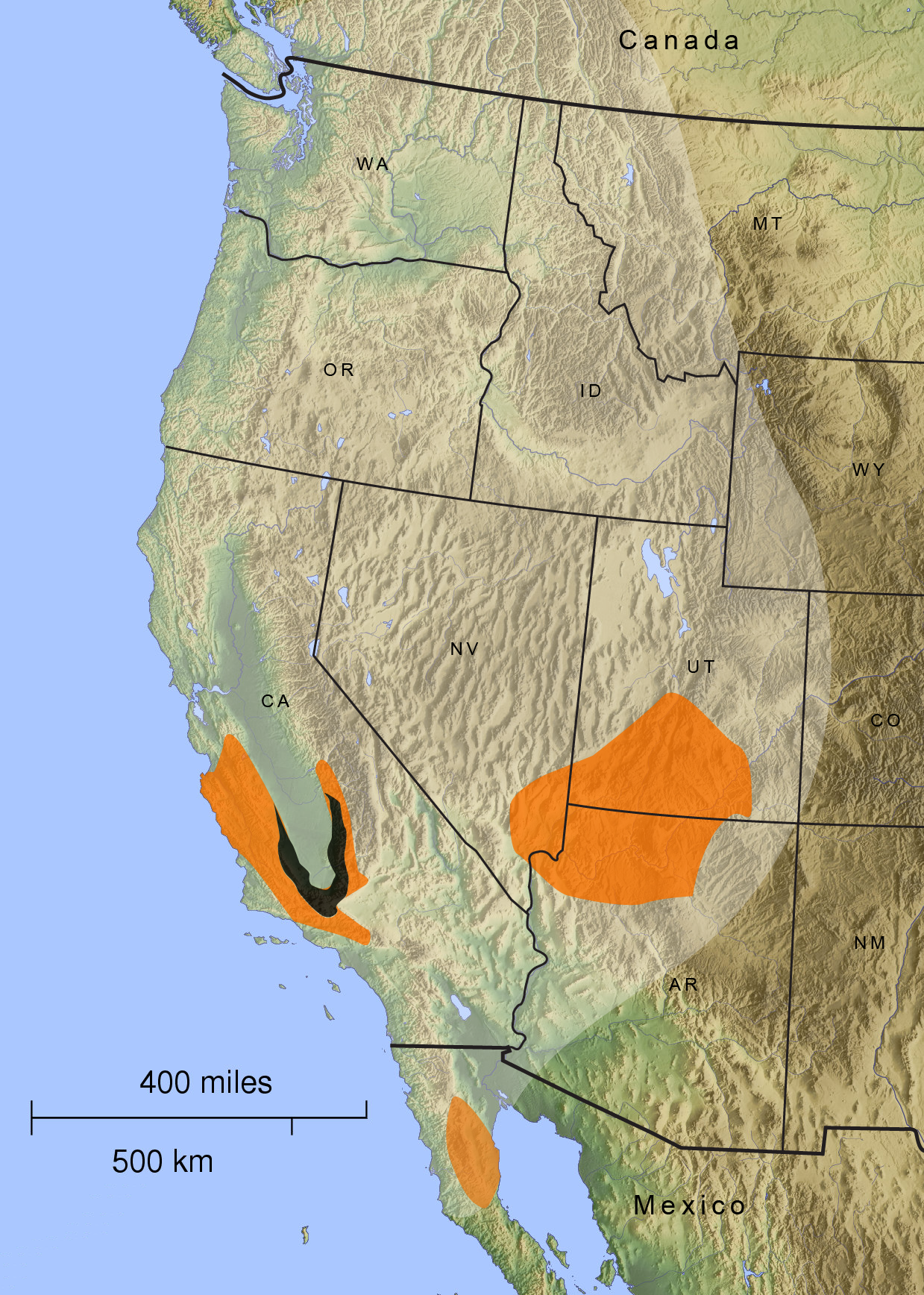

The California condor once inhabited most of the West (see map). Like most ecocide, the decline of the California condor began with settler-colonialism. Around the turn of the century, invading miners and settlers began shooting these birds to use their feathers in the gold-mining process. Condors also died off due to lead poisoning from eating carrion that settlers had shot with lead bullets.

Captain Bloodderivative work by Gretarsson, via Wikimedia Commons

This bird had a variety of roles in countless Indigenous tribal stories. Many of these roles are tied to creation stories. In stories of the Wiyot Tribe, the condor is a life-giver. For the Mono, the condor brings the destruction needed before regeneration. One story, from the Yokut people, recounts how the condor ate the moon and created the lunar cycle. In the Chumash creation story, the Sky Snake (the Milky Way) gave humans the gift of fire. According to the story, the condor had white feathers at the time. Ever curious, the condor flew down to see the fires now being used by humans, only to accidentally scorch his feathers black—explaining the condor's distinctive coloration, with the white bands under his wings being the only part not to be burned.

The restoration of wild condor populations would not have happened without Indigenous-led efforts. The Yurok Tribe has worked tirelessly over the past decades to restore its prairies, forests, and rivers. “Bringing a species like California condor, pregoneesh, back to our ancestral territory… that’s a huge reparation in the wound that the Yurok people and all tribes in this area have suffered since contact and the disruption to our eco-region,” Yurok wildlife department director Tanya Williams-Claussen said in an interview. “To know that we’re restoring them to Yurok ancestral territory, and this is restoring an integral and indescribable part of our spiritual and ecological community—it’s a really big deal.”

Right on schedule, the first California Condors were released on May 3rd of this year. The tribe is collaborating to monitor the reintroduction's impact on the ecosystem for the next three years. If all goes well, this massive bird will become a more common sight, reminding people of their history and empowering them to revive their traditions.